This section presents the findings of the research with respect to relevance; design, delivery and cost-effectiveness; and success.

To determine the relevance of the federal participation in the TWRI, the evaluation was structured so as to provide insight to the following two questions:

Overall, the evaluation found that both the TWRI and its funded projects were consistent with federal priorities, and that there was a demonstrated need for federal funding in the revitalization of the Toronto waterfront.

Federal participation in the TWRI is consistent with the historic role of the federal government in similar large-scale projects in other Canadian cities. The Government of Canada has a long history of funding infrastructure projects. This has included federal support for recent waterfront revitalization projects in other Canadian cities, including:

Federal government support is also consistent with support from federal governments for similar waterfront revitalization projects in other areas of the world including London, UK.

The federal participation in the TWRI is aligned with current federal priorities. According to the 2007 Speech from the Throne, the federal government of Canada has outlined its commitment to infrastructure funding in order to address its priority of "providing effective economic leadership."5 Another federal priority outlined in the speech is "improving the environment," which is consistent with the environmental objectives of the TWRI.

Key informants from the TWRC and the three orders of government interviewed for this report felt that there was a demonstrated need for the federal government's participation in the waterfront revitalization. It was felt that without federal participation, the revitalization would have lacked sufficient financial resources, and would have lacked the credibility and exposure that comes from having all three orders of government involved. In addition, the involvement of all three orders of government was felt to be vital to facilitating effective planning and coordination.

Further, several federal departments have held responsibility for a share of the land in the Toronto waterfront area. Properties of direct or indirect interest to the federal government in the Toronto waterfront area have included the Toronto Port and 11 other properties, including holdings by the department of Public Works and Government Services (PWGSC), the department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), the department of National Defence (DND), and Canada Post. This land has been estimated to occupy approximately six per cent of the total waterfront land.

While the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative has been consistent with overall Government of Canada priorities, federal participation in the Initiative has not always been consistent with the responsibilities of the five departments where the Initiative has resided since 2000. Responsibility for the Secretariat currently rests with Environment Canada, whose mandate to preserve and enhance the quality of the natural environment and to protect Canada's water resources is in line with the goals of the Initiative. Since 2002, however, large-scale federal infrastructure funding initiatives have been the responsibility of Infrastructure Canada, a department within the Government of Canada's Transport, Infrastructure and Communities portfolio. Under this portfolio, the federal government has recently launched its infrastructure plan, Building Canada, which commits $33 billion to infrastructure spending from 2007 to 2014. Prior to 2002, the federal investment in infrastructure was centred in the Canada Infrastructure Works Program, which later became Infrastructure Canada.

The original goal of the federal participation in the TWRI was "to position Canada, Ontario and Toronto in the new economy, thus ensuring Canada's continued success in the global economy." The goals also included "the enhancement of the quality of life in Toronto, and the encouragement of sustainable urban development."

Originally, federal government funding was often focused on projects related to transportation infrastructure, as evidenced by funded projects like the Front Street Extension and the Union Station Second Platform, among others.

In January of 2004, then Prime Minister Paul Martin asked Toronto Member of Parliament Dennis Mills to review the progress of the TWRI and to draft a list of immediate deliverables on the waterfront. The findings were presented in Mills' report Building on the Green Footsteps. According to the federal government's response to the report "...the main premise of the Mills recommendation package is that the waterfront should be a green and accessible space open to all citizens, and that sports, recreation and culture/tourism should serve as a prime attraction to bring people back to the lakeshore."6

In May 2004, the federal government signalled the addition of parks, recreation and public spaces as a funding priority within the federal TWRI, although it continues to fund projects within other waterfront revitalization priorities.7 The identification of priority areas by each order of government was designed to guide the planning of future funding allocations.

While some of the expected outcomes and performance indicators detailed in the federal government's TWRI RMAF and logic model relate somewhat to these funding priorities, none of the outcomes statements are directly aligned with these priorities. This suggests that some of the outcomes identified in the performance measurement documentation could be revised in light of evolving federal priorities in the TWRI.

The design, delivery and cost-effectiveness of the TWRI were examined in relation to the following questions:

The evaluation found that the use of a corporation to manage complex revitalization activities is a common and appropriate method, although issues were identified with respect to the timeliness of revitalization activities and the lack of private sector involvement in revitalization activities to date. The TWRI does not appear to duplicate the work of other initiatives, although infrastructure funding by the federal government is generally concentrated within the department of Infrastructure Canada, which delivers funding with partner departments and organizations.

While the use of a contribution program to deliver TWRI funding has resulted in considerable administration on the part of the TWRC, it is not clear that another delivery mechanism would have been an appropriate alternative for the initiative. Further, the federal TWRI Secretariat appears to demonstrate value-for-money. Concerns about the appropriateness of indemnification requirements and the TWRI governance were noted in the research.

A review of alternative delivery models was undertaken for the TWRC in 2004.8 In this review, it was found that a corporation model was used in most of the 27 reviewed jurisdictions that undertook large-scale revitalization. As part of this evaluation, the Forks (Winnipeg, MB), Halifax waterfront (Nova Scotia), London Docklands (London, UK) and Sydney harbour (Australia) revitalization activities were further reviewed. The development corporations that coordinate and implement development in these four jurisdictions are described below. Further information on the comparison sites is provided in Annex 5.

Similar to the TWRC, development corporations in Halifax and Winnipeg were provided with federal funding when first established. The London Docklands development project was also funded through its central government through a £1.86-billion investment from the British government.9

Clearly the use of a development corporation, with initial federal funding, is a common method for managing complex revitalization activities. Further, the use of such an entity has helped to alleviate the historic barriers to waterfront revitalization identified in the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Task Force report of 2000. These barriers included a lack of an agreed vision among governments and the public on the future of the waterfront, and the lack of a vehicle for the comprehensive management of renewal. TWRC activities have been effective at engaging the public and building a public dialogue and vision for the waterfront, and the TWRC is an appropriate vehicle for moving forward with that vision.

The TWRC has faced significant challenges resulting from the complexity of revitalization activities involving multiple governments and a range of other stakeholders in the waterfront area. This has resulted in delays in the development of contribution agreements, as well as in the commencement or completion of projects. The three orders of government are working with the TWRC to develop practices and processes that are intended to improve the pace of revitalization, and improve project and financial management.

This evaluation also noted some concern with respect to TWRC governance. Key informants interviewed for this evaluation, as well as the review of TWRC governance structures undertaken by Mercer Delta Organizational Consulting in 2004, noted the risk of the politicization of the TWRC Board of Directors through the ability of the provincial and municipal governments to appoint elected politicians as members. The federal government, according to the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation Act, 2002, is not able to appoint elected political officials. This results in a degree of asymmetry between the three governments and the TWRC.

Generating Revenue and Private Investment

The original task force report estimated the total costs for the renewal of the waterfront at approximately $12 billion,10 and the TWRC later estimated renewal would cost approximately $17 billion over 30 years. The three governments have committed $1.5 billion, leaving a sizeable gap for the TWRC to bridge through revenue-generating activities or by utilizing private sector investment.

To date, federal funding for the TWRC has not resulted in the leveraging of private sector funding for waterfront revitalization. This was noted in the value-for-money audit and organizational review of the corporation commissioned by Oliver Wyman (Delta Organization and Leadership Ltd.) in partnership with Horwath Orenstein LLP, released in 2007.11 In June 2007, the City of Toronto made the release of 2008 City of Toronto TWRI funding conditional on the TWRC developing a revenue-generating strategy and on the endorsement of the strategy by the IGSC. The TWRC is currently developing its revenue strategy.

Interviews with stakeholders indicated that the TWRC expects to generate the majority of its revenue through land sales. In the case of brownfields (where expansion or redevelopment is complicated by contamination), concerns about cleanup liability pile on top of other burdens (such as old infrastructure).12 This can make waterfront development a particularly risky venture for private investors. The TWRC's approach to enticing private sector interest was said to involve the absorption of some of these risks by making initial investments in infrastructure, flood protection, soil remediation, parks and open space, and planning and zoning.

According to the TWRC's Development Plan and Business Strategy, it is estimated that the government will receive an annual rate of return on its investment in the order of 14%. It is expected that the waterfront revitalization will attract an additional $13 billion in private sector investment over a 30-year timeframe.13

Some initial activity in this area was noted. The TWRC is working to finalize the design plan for a major new office and broadcast headquarters for Corus Entertainment. It is expected that this project will spur further private sector interest and development in the East Bayfront area.

Until recently, the TWRC, under its Act, was restricted in its powers to generate revenue. The Act stated that the Corporation could not borrow money or raise revenue unless it had the consent of the federal government, the provincial government, and the City of Toronto or unless it was authorized to do so by a regulation. This restriction to raise revenue was substantially eliminated in 2007.

Other development corporations that were reviewed for this evaluation were highly successful in generating revenue and private investment in the long term. For instance, Waterfront Development Corporation Limited in Halifax received $1.6 million in private investments in 2004, compared to a public investment of $2.3 million. Its goal is to generate a return of $20 to the province for every $1 spent by the corporation. Additionally, according to an economic impact study conducted for the Halifax corporation, the net economic impact of the Waterfront Development Corporation Ltd. in 2001 was estimated at $89.6 million in household income and $144 million in gross domestic product (GDP)14. The majority of the corporation's revenue flows from the leasing and sale of land and commercial space. The London Docklands development also generated sizeable private investments. The £200-million Lewisham extension was funded entirely by the private sector, and the London Docklands Development Corporation (through its £1.86-billion investment of public money) leveraged £7.2 billion of employment-generating private investment (hotels, restaurants, shops, factories, print works, offices, leisure facilities) from 1981 to 2001.15 The London Docklands Development Corporation has also generated over £4.7 million from land sales over its 18-year history.

It should be noted, however, that development corporations reviewed for this evaluation did not immediately attract private sector involvement in revitalization. For instance, it took the Waterfront Development Corporation in Halifax approximately 10 years to leverage significant private funds, and a similar timeframe was evidenced in the Forks development in Winnipeg. The £200-million Lewisham extension in the London Docklands (one of the first major infrastructure projects that was wholly funded by the private sector in the area) did not begin construction until 1996, 16 years after the corporation's establishment.16

Governmental oversight for the TWRI is provided through the Intergovernmental Steering Committee (IGSC). The IGSC established an Operations Working Group to manage TWRI contribution agreements across the three orders of government.

The review of the governance structures and delivery models undertaken in 2004 by Mercer Delta Organizational Consulting noted a lack of clarity and definition regarding the role of the IGSC.17 Key informants interviewed for this evaluation also noted that the IGSC has not been an effective venue for government oversight of the TWRI. This was felt to be the result of the infrequency of meetings and the frequent changes in membership because of changes in senior federal management. However, key informants were positive about the extent to which the Operations Working Group had fulfilled its mandate of overseeing the coordination and management of contribution agreements.

According to Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Policy on Transfer Payments, all contribution agreements must include an indemnification clause.18 An indemnity clause is a provision where one party undertakes to accept any responsibility for losses or damages another party may suffer or be liable for. This usually refers to the obligation to pay money to compensate for damages suffered by a first or third party.19 In the case of the TWRI, the indemnity clause (clause 25) ensures that the Crown (the federal government) is secured against future loss, damage, or liability when it enters into a contribution agreement with the TWRC. However, the TWRI contribution agreement template includes two additional sub-clauses (12.3 and 12.4) that hold eligible recipients and third party contractors contracted by the TWRC responsible for any claims, liabilities and demands resulting from injury, damage or loss of property.

According to key informants, the inclusion of clauses 12.3 and 12.4 stemmed from the perceived higher degree of risk associated with initial TWRI projects, given the youth and small size of the TWRC during the early stages of the TWRI.

Several key informants noted that these additional indemnification requirements have been problematic. Third parties being contracted by the TWRC to undertake TWRI projects were said to have sometimes charged premiums to cover the liability requirements, while other contractors have refused to agree to these indemnification requirements.

In late 2006, the TWRC commissioned a review and report on strategies for managing the operational risks of the Toronto waterfront revitalization. The report set forth recommendations for moving forward on amending the risk management between the three orders of government and the TWRC. The TWRC and its government funders are working to modify current indemnification requirements.

At the time of this evaluation, the federal TWRI Secretariat, headed by a Director, consisted of 12 full-time equivalent positions. In 2006-2007, it cost the federal TWRI Secretariat two cents of operations and maintenance (O&M) expenses to deliver every dollar of contribution funding. For the total of the years 2004-2005 to 2006-2007, it cost three cents to deliver every dollar (Table 2).

Year |

O&M |

Grants and Contributions |

|---|---|---|

2001-2002 |

O&M expenditures were cash-managed by the respective departments and not tracked separately for the TWRI. |

$500,000 |

2002-2003 |

$5,200,000 |

|

2003-2004 |

$6,177,365 |

|

2004-2005 |

$690,178 |

$15,588,910 |

2005-2006 |

$764,761 |

$32,274,039 |

2006-2007 |

$622,793 |

$31,450,174 |

2007-2008 |

$671,397 |

$32,664,347 |

Total: 2004-05 to 2007-08 |

$2,749,129 |

$123,854,835 |

a Source: Federal TWRI Secretariat, Environment Canada

For comparison, the ratio of O&M to G&C expenditures was calculated for the department of Infrastructure Canada. Based on its expenditures for 2006-2007, it cost two cents for the department to deliver each dollar of infrastructure-funding.20 It should be noted that there are limitations to this comparison. For example, while Infrastructure Canada delivers grants and contributions under a series of different funding programs, this funding is implemented through assistance from other federal agencies, depending on the project. Ongoing monitoring is a shared responsibility between Infrastructure Canada and its implementation partner, whereas the federal TWRI Secretariat is solely responsible for monitoring contribution agreements with the TWRC. In this context, the ratio of O&M to G&C expenditures within the federal TWRI Secretariat appears to be cost-effective.

Current Delivery Structure

The use of a contribution program to deliver TWRI funding has allowed the federal government oversight of its funding contribution, including control of how the funding is spent and the ability to monitor progress towards achieving the expected funding results. As revitalization plans and project implementation have proceeded incrementally, the use of contribution agreements has ensured that projects are funded incrementally through consecutive agreements and according to their terms and conditions.

TWRI projects are currently funded by the federal government through contribution agreements with the TWRC. Projects may consist of separate agreements for planning and design, environmental assessments, and/or implementation components. At the time of the evaluation, the federal government had 32 contribution agreements with the TWRC, with a total value of approximately $231 million. As illustrated in Table 3, the amount of federal funding being spent increased significantly in 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 as many projects began to move from the design/planning phase to implementation.

| Maximum federal funding | $410,000,000 |

|

|---|---|---|

Federal funding by year |

2001-2002 |

$500,000 |

2002-2003 |

$5,200,000 |

|

2003-2004 |

$6,177,365 |

|

2004-2005b |

$16,279,088 |

|

2005-2006b |

$33,038,800 |

|

2006-2007b |

$32,072,967 |

|

2007-2008 (end of Q3) |

$33,335,744 |

|

| Total federal funding expended to date | $126,603,964 |

|

| Total federal funding remaining | $283,396,036 |

|

| Amount remaining in 2007-2008 reference level (end of third quarter) | $50,392,651 |

|

| Forecasted expenditure 2008-2009 | $233,003,385 |

|

a Source: Federal TWRI Secretariat, Environment Canada

b Includes operating expenses. Operating expenses from 2001-2004 were cash-managed by the respective departments.

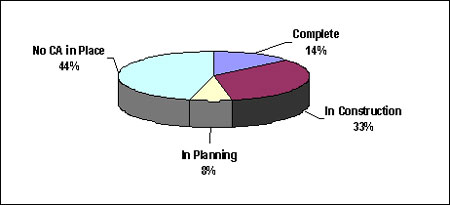

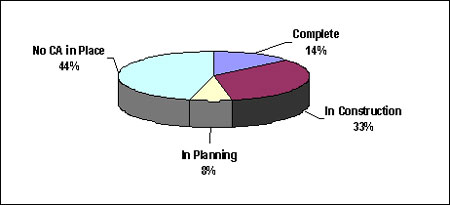

At the time of the evaluation, there were no contribution agreements in place for approximately 44% of the federal government's investment in the TWRI. Figure 1 illustrates the extent to which planned funding has been allocated.

Figure 1. Distribution of Federal Government Investment in TWRI Projects by Completion Statusa, b, c

a Source: Federal TWRI Secretariat, Environment Canada

b Federal amount allocated in the 2007-2008 tri-governmental long-term funding plan: $410 M

c Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding

The development of contribution agreements has taken considerable time. Many key informants noted that the process of the TWRC developing contribution agreement proposals, often for funding from more than one government, has been slow and has resulted in considerable delays in commencing revitalization activities. Key informants also noted that the process of contribution agreements obtaining ministerial approval has, at times, required considerable time. As noted in the recent Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contribution Programs, this is a common concern with many contribution programs.21

Many of the particular challenges to the use of a contribution program for the TWRI have resulted from the relatively large number of agreements, and the involvement of multiple government funders. This inherent complexity appears to have been exacerbated by the fact that the TWRC has required time to establish and develop its human resources and operational capacity. The government approval process for contribution agreements has been perceived by key informants to have, at times, lengthened the time required to commence projects. The TWRC and its three government funders have developed a work plan to improve the process's timeliness and effectiveness in the future.

Further, a Tri-government Long-term Funding Plan was developed and approved by all orders of government to allocate the majority of each government's $500 million commitment. The three orders of government reviewed the Long-term Funding Plan in 2006 and 2007 to reflect current realities. The development of a long-term funding plan, with milestones and priorities, was undertaken to provide a roadmap for future funding to the TWRC.

Currently, federal contribution agreements cannot exceed $10 million without Treasury Board approval, despite the federal TWRI Secretariat’s efforts to have the threshold removed in 2007. This threshold may act as a hindrance to the efficient delivery of the remaining federal funding before the current federal sunset date of 2010–2011. Given the existence of a Long-term Funding Plan, it may be possible to allocate future TWRI funding through larger value contribution agreements in order to reduce the number of separate contribution agreements, while still ensuring federal oversight of project funding. In light of the plan and considerable federal oversight of contribution agreements through the Operations Working Group, the appropriateness of the $10 million should be re-examined.

Alternative Delivery Mechanisms

As outlined in the TBS Policy on Transfer Payments, transfer payments can be undertaken through contributions, grants and other transfer payments. All types of transfer payment programs require meeting TBS guidelines on due diligence. Contributions are subject to being audited and accounted for, whereas grants are not, although grants may be verified for eligibility and entitlement and grant recipients must meet specified pre-conditions. Other transfer payments are payments based on legislation or on arrangements such as a formula or schedule, and include transfers to other orders of government such as used for equalization payments.

Numerous key informants at the TWRC suggested that federal government funding for the TWRI be undertaken through grant funding. Grants do not require as significant a degree of accountability and reporting, and would allow funds to be allocated in different ways as projects evolve. Grants could be utilized for a "block" funding approach to revitalization of the waterfront, rather than project-specific funding as is currently practiced through contribution agreements. Key informants had different ideas on how a grant funding approach could be undertaken. However, it should be noted that according to TBS policy, all assistance to a recipient's capital projects must be in the form of a contribution, not a grant, unless otherwise approved by the Treasury Board.22 Further, given the considerable time that TWRI funding has been delivered through a contribution program, it is not known to what extent the use of grant funding at this stage could result in faster revitalization activities. New processes would have to be developed to administer a grant program, and, as noted in the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contribution Programs, grant programs can require similar administrative requirements as contribution programs.23

Currently, the TWRI is the major vehicle for Toronto's waterfront revitalization. No major duplication was noted with other initiatives in the area.

Federal infrastructure programs and issues are the primary responsibility of Infrastructure Canada. Situating the federal TWRI Secretariat within other departments has separated the program from other federal infrastructure programs, and has resulted in the Secretariat being housed in departments with dissimilar objectives and mandates. As one key informant noted, "Environment Canada is a better fit than other departments, but it is not the best fit."

Infrastructure Canada has an array of funding programs for infrastructure, many of which have included funding for parks and waterfronts. This includes the Canada Strategic Infrastructure Fund (CSIF), which has funded infrastructure projects similar to that provided through the TWRI. For example, in 2004, the CSIF provided $60 million to assist in the clean up of Halifax Harbour. In the same year, an announced commitment of $47.5 million was made for development of public infrastructure at Mont Tremblant, including roadways, waterworks and sewer systems, sidewalks and multifunctional paths (cross-country skiing, cycling, hiking, etc.). Similar to the floodplain developments for the Lower Don in Toronto, the CSIF provided $40 million in federal funding to remediate the floodplain where the Assiniboine and Red rivers merge into Lake Winnipeg. Further, in 2004, $65 million of TWRI funds were transferred to Infrastructure Canada under the CSIF for improvements to GO Transit in Toronto.

Additionally, Infrastructure Canada's Building Canada plan will commit approximately $33 billion for provincial, territorial and municipal infrastructure between 2007 and 2014. The Spadina Subway Extension in Toronto is planned to receive federal dollars through the Building Canada Fund, a targeted infrastructure program through the Building Canada plan. Additional base funding is provided to provincial governments through the provincial/territorial component of the Building Canada plan. Terms and conditions have yet to be developed for the program but staff at Infrastructure Canada suggested that the plan may operate as a contribution program with maximum federal funding per project set at $20 million.

The success of the TWRI was examined in relation to the following evaluation questions:

The evaluation found that while the TWRI had made progress in planning, design and land preparation, major work in implementing construction activities was only beginning to be carried out by the TWRC. Some initial construction projects are completed or in progress, largely related to the federal funding priorities of public parks and recreational spaces. As a result, the outcomes explored here do not cover all those identified in the TWRI logic model; a more comprehensive exploration of expected outcomes should be undertaken, once the implementation phase is completed.

The evaluation found that revitalization has demonstrated sound environmental processes, and was resulting in improved environmental management in the waterfront area. The TWRI had also fostered greater community awareness and participation in waterfront revitalization activities, and some preliminary improvements to usage, accessibility and economic activity in the waterfront area were noted.

Project work completed to date has resulted in some progress in revitalization activities. Many of these have involved planning but the focus of TWRI activity is now increasingly shifting to implementation. A full description of individual TWRI projects and their federal funding allocations is provided in Annex 6. Of the 28 funded projects, seven are in the close-out process, including five that are completed projects. These projects include:

Further, a feasibility study related to the potential construction of a Discovery Centre has been completed. Following the completion of the study, the federal government decided not to proceed with construction of the centre. The Discovery Centre was the subject of opposition among some community members, including the community group "Friends of the Spit," largely due to what was considered its disproportionately large size for its proposed site.

In addition to completed projects, several large public spaces and parks are currently in construction and are planned for completion in 2008. These include:

Timelines for project deliverables are outlined in contribution agreements with the TWRC, with project timelines also outlined in TWRC planning documents. In many cases, the completion of TWRC projects has not proceeded as originally planned. For example, construction of a second subway platform at Union Station to alleviate passenger congestion was first proposed in 2002 and was to be completed in 2008. Work on the platform is now scheduled for completion in 2011.24

Project schedule overruns have been the result of a number of factors. Primarily, it would appear that the length of time required to complete projects has been consistently underestimated, a point noted by several key informants in interviews. Further, the nature of multi-governmental funding agreements is inherently complex, requiring significant time. A challenge for the TWRC has been addressing the demands of its three government funders, each with its own funding management requirements. Projects have also involved extensive stakeholder and public consultations. Further, tri-governmental environmental assessments for more complex projects can take considerable time to complete. In addition to the time necessary for the fulfilment of these various project requirements, key informants also noted a number of delays stemming from stalled negotiations over land acquisition and indemnity requirements. The additional indemnity requirements for contractors working on TWRI projects were said to have complicated the bidding process, and were perceived to have resulted in some delays to project work.

A 2007 Value-for-Money Audit and Organizational Review commissioned by the TWRC Board of Directors made specific recommendations aimed at improving the timeliness of project development, implementation and management. The recommendations included additional staff at the TWRC to deal with the current and expected volume of work.25 Based on these recommendations, an intergovernmental work plan has been developed that identifies responsibilities and next steps meant to allow the Corporation and the three governments to improve revitalization activities. Among the steps included in the work plan are:

In 2005, HRSDC undertook an audit in order to determine if the TWRC had complied with the terms and conditions of federal contribution agreements for four priority projects (including the Union Station Second Platform, Portlands Preparation, Front Street Extension, and Lower Don River Environmental Assessments, as well as the Waterfront Toronto Development Plan and Business Strategy) over the period of November 2001 to March 31, 2004.26 The audit noted that not all of the terms and conditions of the contribution agreement had been met by the TWRC, such as $2 million in unallocated corporate costs (e.g., office overhead, salaries) that were not covered by contribution agreement. The audit also noted that the contribution agreement did not state projected milestones and anticipated dates of achievement, and it noted incomplete or delayed information in the TWRC's Internal Control Framework, including inconsistencies in reporting financial data. The audit also noted projects that were awarded to third-party contractors by the TWRC without a competitive process despite stipulations in the contribution agreements that this be the case for contracts in excess of $75,000. The federal TWRI Secretariat developed an action plan to respond to these findings, but noted that many of the issues raised in the audit were being addressed at that time with the TWRC as a result of ongoing monitoring of contribution agreements.

As most of the TWRI project work completed to date has involved planning, design, and environmental assessments, it is premature to assess the full impact of the federal TWRI on economic development and economic opportunities. While some initial positive impacts have resulted from the completion of the Western Beaches Watercourse Facility and other projects, additional work should be conducted to measure the achievements and success of all federal funding once the project implementation phase is completed.

Some preliminary economic impacts of the federal participation in the TWRI have been examined through the evaluation's survey of businesses, from an economic impact study of the Western Beaches Watercourse Facility, and through examining City of Toronto employment data for the waterfront area. Overall, the outcomes of these measures demonstrate that the TWRI has yet to have a significant impact on economic development in the area.

Key informants were generally positive about the potential economic impact of the federal TWRI activities, but felt the impact would be seen following the completion of more significant construction projects. Experts in urban development from academia believed that the TWRI would eventually increase the level of economic activity in Toronto's waterfront area, but concern was expressed by two experts over the absence of an explicit employment strategy for the entire waterfront area. It was felt that commercial development alone was not enough to draw employers to the waterfront.

Brownfields Redevelopment and Commercial Development

Brownfields are defined as "abandoned, vacant, derelict or under-utilized commercial land or industrial properties where past actions have resulted in actual or perceived contamination."27 The federal government has recognized the economic benefits from brownfield redevelopment: it has identified the potential economic benefits from developing brownfields in its 2001 budget and in 2003 it tasked the National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE) to prepare a National Brownfield Redevelopment Strategy.28 In a separate study conducted by Christopher DeSousa, annual potential public benefits resulting from brownfield development in the Greater Toronto area were estimated at between $15.6 million and $31.7 million in 2002 dollars.29 The majority of brownfields in the waterfront area are located in the Port Lands (approximately 285 ha [700 acres]) and at the site of the planned Lake Ontario Park (approximately 325 ha [800 acres]). According to TWRI project files, 3.67 ha (9.08 acres) of brownfields were remediated for the transitional/interim sports fields in the Port Lands. The total area of brownfields that are planned for remediation in the waterfront area is provided in Table 4.

Total Area |

|

|---|---|

| West Don Lands | 35 ha (90 acres) |

| East Bayfront | 30 ha (80 acres) |

| Port Lands | 285 ha (700 acres) |

| Lake Ontario Park | 325 ha (800 acres) |

| Total | 675 ha (1,670 acres) |

a Source: TWRI and TWRC project files

It is not clear at this point to what extent the federal government's participation in the TWRI will involve brownfield remediation activities. Several planned projects that will involve federal funding, including construction of Lake Ontario Park and the Central Waterfront Public Realm, are located on lands that contain brownfields.

Further, the federal government was involved in funding a Precinct Plan for the East Bayfront area. According to the Precinct Plan, this area is expected to eventually house approximately 185,000 m2 (2,000,000 sq. ft.) of commercial space (equivalent to space for 8,000 employees). Precinct planning looks at specific areas of the waterfront to define the location and character of parks, public spaces and promenades, streets and blocks, building form and location, transportation and public facilities. It is the final planning step prior to the design and construction stage.

Western Beaches Watercourse Facility

The Western Beaches Watercourse Facility was completed in 2006 and hosted the International Dragon Boat Championships held that same year. According to an economic impact study conducted by the Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance, the event produced considerable economic benefits.30 Surveys were undertaken with visitors, participants and employees to calculate expenditures and average spending amounts.

A total of $9.4 million in wages and salaries were paid in the Toronto area through the creation of an estimated 177 jobs, with an additional $5.1 million paid throughout the rest of the province. Overall, the event is estimated to have generated more than $24.2 million in gross domestic product (new economic activity), of which nearly $15.5 million occurred in Toronto. The International Dragon Boat Championships also generated sizeable tax revenue, at nearly $8.7 million, of which $4.2 million was accrued by the federal government.

City of Toronto Employment Data

Employment data were provided by the City of Toronto (Table 5). These were extracted using the same geographical parameters (by forward sortation area) as the survey of businesses undertaken for this evaluation. For comparison, data were also provided for the entire city of Toronto.

According to this data, employment in the waterfront area remained largely unchanged between 2000 and 2006, with a small decrease in employment and business establishments. This was consistent with the trend seen during the same period for the entire city of Toronto. It is reasonable to assume that TWRI has, as yet, had little impact on employment in the waterfront area.

| Year | Waterfront Area | City of Toronto | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Employed | Number of Establishments | Total Employed | Number of Establishments | |

| 2000 | 180,170 |

7,542 |

1,288,386 |

73,217 |

| 2001 | 179,914 |

7,266 |

1,286,343 |

72,477 |

| 2002 | 179,503 |

6,722 |

1,261,910 |

72,250 |

| 2003 | 173,440 |

6,894 |

1,251,342 |

71,813 |

| 2004 | 173,249 |

6,842 |

1,255,598 |

71,617 |

| 2005 | 176,023 |

6,648 |

1,262,653 |

71,509 |

| 2006 | 179,503 |

6,722 |

1,276,726 |

72,935 |

| Difference between 2000 and 2006 | -667 |

-820 |

-11,660 |

-282 |

| % change, 2000-2006 | -0.4% |

-10.9% |

-0.9% |

-0.4% |

a Source: City of Toronto Employment Survey 1997-2006

Economic Impacts based on Survey of Businesses

A survey of businesses in the waterfront area was undertaken in order to gather perspectives on the perceived impact of the TWRI to date. Consistent with findings from the analysis of City of Toronto data, most businesses felt that the current revitalization initiatives on the Toronto waterfront had not had an impact on their business activities. Given that few construction projects have been completed to date, it is not unexpected that business attribution of positive impacts would not be high at this point.

Relative to other business respondents in other areas of the waterfront, respondents with businesses operating in the John Quay and York Quay area (who said they were aware of TWRI activities) were more likely to state they have seen improvements in their business as a result of waterfront revitalization. However, the difference between John Quay and York Quay business owners and those in the remainder of the waterfront area was more modest when respondents were asked to anticipate future positive benefits as a result of waterfront revitalization. Findings from the business survey, shown in Table 6, include the following:

| John Quay and York Quay Area | Remainder of Waterfront Area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree/ Disagree | Neutral | Agree/ Strongly Agree | Strongly Disagree/ Disagree | Neutral | Agree/ Strongly Agree | |

| The revitalization of the Toronto waterfront is good for my business. | 16% |

29% |

56%a |

18% |

35% |

47% |

| I anticipate future growth to my business as a result of the revitalization of the waterfront. | 36% |

23% |

41% |

40% |

24% |

36% |

| The waterfront revitalization has had a positive impact on my business. | 30% |

34% |

36% |

29% |

54% |

17% |

| The proposed improvements to the Toronto waterfront will increase the number of customers/clients who visit my place of business. | 44% |

22% |

35%b |

48% |

20% |

32% |

| The new parks, promenades and public spaces in the waterfront area have increased the number of customers/clients who visit my place of business. | 52% |

24% |

24% |

62% |

26% |

12% |

a Source: R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. 2007. Business Survey, Toronto.

b n = 166-175; asked only of those respondents aware of the TWRI

c Numbers may not total 100 because of rounding.

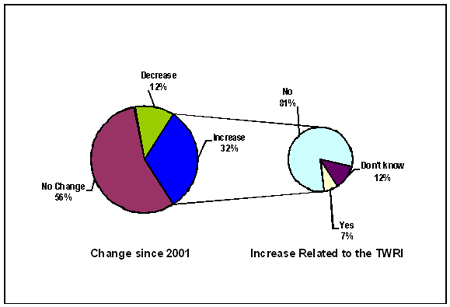

Business survey respondents were also asked if they had seen a change in their business activities since 2001, and if they felt that this change was the result of TWRI activities. As displayed in Figure 2, 56% of respondents who were aware of the TWRI had not witnessed a change in the number of employees at their business since 2001. About one-third (32%) of respondents claimed that there had been an increase in the number of staff they employ, but only 7% felt that this change was related to the waterfront revitalization efforts.

Figure 2. Changes in Businesses' Employment since 2001 and Extent to Which Changes Were Believed to be Related to TWRI Activitiesa, b

a R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. 2007. Business Survey, Toronto.

b n = 57-177

The TWRI has demonstrated sound environmental approaches in revitalization. This is evidenced through the consistent use of an environmental assessment process, through the application of principles of sustainability at the TWRC, and confirmed through focus groups and interviews undertaken for this evaluation. Evidence of planning for improved environment management as a result of the TWRI is demonstrated by projects supporting land intended for flood protection, planning for building units certified as meeting the requirements of the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Green Building Rating System (LEED®), development of parklands and green space, and other evidence of the application of principles of environmental sustainability.

Environmental Assessments

Environmental assessments undertaken by environmental professionals (including the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority and private consultants) have been routine components of federally funded TWRI projects. Environmental assessments are undertaken to determine the environmental impact of projects before they are carried out, and to propose ways of mitigating adverse environmental effects. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) requires that the federal environmental assessment process be applied where the Government of Canada has decision-making authority, whether as a proponent, land manager, source of funding or regulator. In instances where a project requires regulatory approval from other departments (e.g. Fisheries and Oceans as it relates to the Fisheries Act or Transport Canada as it relates to the Navigable Waters Protection Act), the environmental assessment process becomes housed outside of the federal TWRI Secretariat.

Seventeen environmental assessments have been conducted for federally funded TWRI projects.31 These have included environmental assessments for the Harbourfront Centre - John Quay Water's Edge Revitalization, the ShakespeareWorks Theatre Project and the Western Beaches Watercourse Facility. It should be noted that not every federally funded project requires an environmental assessment. Several TWRI projects have been exempt from environmental assessments due to their limited effect on the environment or because they were excluded from assessment under the Exclusion List Regulations, 2007 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act. Further, projects that are explicitly linked to environmental improvement efforts (for example, shoreline protection, dredging) are exempt from assessment.32

The environmental assessment process, from the start date to the determination date, lasts about one month for TWRI projects. Generally, the environmental assessment process took longer for those projects that were both provincially and federally funded, as they were subject to assessments by both orders of government. In comparison to the CEAA, the Ontario Environmental Assessment Act (OEAA) is more of a planning-oriented process. While CEAA requires the submission of an actual project for assessment, an Ontario environmental assessment is required for all activities, proposals, plans or programs undertaken by a public body33. The OEAA therefore encompasses a broader array of initiatives than CEAA34. As a result of its structure and purpose, the OEAA process can also be lengthier than that of the CEAA.

More complex projects (in terms of their technical nature) such as Tommy Thompson Park witnessed a lengthier and more comprehensive environmental assessment process. There were some concerns voiced over the length of the environmental assessment process: two key informants involved in the TWRI noted that the process considerably lengthened the time required prior to commencing project work. The federal TWRI Secretariat, with the other government funders, has responded to this consideration by strategically planning project funding in order to eliminate, to the degree possible, duplication in federal and provincial environmental assessments.

There have been no compliance orders issued to date for infractions associated with environmental mitigation/risk management strategies and site remediation plans.

Sustainability at the TWRC

The TWRC has placed a considerable focus on sustainable and environmentally friendly development approaches. Development undertaken through the TWRC is guided by its sustainability framework.35 Focused around five broad goals, the Sustainability Framework identifies short-, medium- and long-term actions to remediate brownfields, reduce energy consumption, build green buildings, improve air and water quality, expand public transit and develop diverse, vibrant downtown communities. The Sustainability Framework promotes many of the policies contained in the federal government's Sustainable Development Strategies 2004-2009.

Further, a sustainability review was undertaken for the TWRC by Swedish experts in 2004. The review assessed sustainability opportunities across the Toronto waterfront, and undertook a sustainability review of the precinct plans for the West Don Lands and East Don Lands. Based on its review, the panel determined that the TWRC's revitalization efforts were "sound, and, in most ways consistent with high standards for sustainability."36 The precinct plans were also felt to be aligned with sustainability principles.

The TWRC has also developed "green" building requirements for developers bidding on waterfront projects. Known as "green specification,"37 some of these requirements include the following:

The TWRC has formally endorsed the Toronto Waterfront Aquatic Habitat Restoration Strategy, which is an initiative to promote increased aquatic habitat along the waterfront. Additionally, staff members in the TWRC's Planning and Design, Construction and Development departments have undertaken training to become LEED® accredited professionals.

Experts in urban development interviewed for this evaluation also felt that TWRI projects had demonstrated sound environmental approaches. According to one expert in the field of landscape architecture, the TWRI approach to revitalization has "fundamentally followed the principles of sustainable development." Furthermore, key informants were unanimous in their belief that the waterfront initiative demonstrated sound environmental processes in revitalization efforts. According to one interviewee, sustainability was a "key requirement. [The TWRC sets] standards for sustainability that exceed the norm."

Community and neighbourhood organization members who participated in focus groups for this evaluation also generally felt that the TWRI activities had been conducted and planned in a way that was environmentally friendly and promoted sustainability. While some participants voiced concerns over whether the overall vision for the waterfront had achieved the appropriate balance between development and green space, most felt that the work being done was exemplary in terms of its use of environmentally friendly approaches.

Improved Environmental Management in the Waterfront Area

Evidence of improved environmental management for completed federally funded project work is highlighted in Table 7. As shown, this has included significant shoreline restoration and improvements.

| Project Name | Description of Completed Activities |

|---|---|

| Port Union Waterfront Improvements |

|

| Western Beaches Watercourse Facility |

|

| Port Lands Beautification: 1. Leslie/Unwin/Cherry streets |

|

| 2. Cherry Beach |

|

| Mimico Waterfront Linear Park |

|

| Tommy Thompson Park |

|

| Harbourfront Water's Edge (John Quay and York Quay) |

|

a Source: TWRC

The federal government has committed funding for two environmental assessments in the Lower Don River area: the Remedial Flood Protection Project and the Don Mouth Renaturalization. The Lower Don River West Remedial Flood Protection Project involves the production of a flood protection solution that will protect human life and infrastructure from flooding by permanently removing approximately 210 ha (520 acres) of Toronto from the Regulatory Floodplain, west and north of the Don River Mouth. The Don Mouth Naturalization and Port Lands Flood Protection Project will involve detailed land-use planning and environmental studies to devise the best solution to re-establish a natural, functioning wetland at the mouth of the Don River, while providing flood protection to approximately 230 ha (570 acres) of land south and east of the existing Keating Channel.

All public and private buildings constructed as part of the TWRI will be subject to LEED® certification. LEED® is an international third-party building assessment and certification tool that is administered in Canada by the Canada Green Building Council. The prerequisites and credits are organized into five principal categories: Sustainable Sites, Water Efficiency, Energy and Atmosphere, Materials and Resources and Indoor Environmental Quality.41 Public buildings will be certified at a "gold" level and private buildings will be certified at a "silver" level.

Additionally, the TWRC's sustainability framework identifies specific objectives to "minimize car use" and "increase walking, cycling and public transit use." Many planned TWRI projects are mixed-use development - meaning that instead of only one use (e.g. residential, commercial, industrial, etc.) in an area, a mix of more than one is preferable.42 Mixed-used development is often used as a key component of "Smart Growth" strategies or as part of transit-oriented development. Benefits of mixed-use can include reductions in auto-dependence, the creation of 'community-oriented' space, and urban revitalization. The Precinct Plans for both the West Don Lands and East Bayfront have established an overall vision for mixed-use development in these areas.

The TWRI has fostered greater community awareness and participation in waterfront planning and implementation. This is evidenced through the significant public and stakeholder consultations carried out by the TWRC and the considerable media interest in waterfront revitalization activities. Focus groups participants from community organizations and key informants were also positive about the degree to which the TWRI had fostered greater community awareness and participation. There was, however, a comparatively lower level of awareness and sense of participation shown among residents and businesses.

Public and Stakeholder Consultations

The TWRC consultations have included both public and stakeholder consultations, as well as its Board of Directors Annual General Meeting, which is open to the public. Public consultations are also undertaken for precinct plans and for environmental assessments. The TWRC website is also a readily accessible source of information on waterfront revitalization. The TWRC has released media releases and newsletters, and has an email mailing list of those who attend public meetings and the website. Further, its Design Review Panel is open to the public.

Individuals from the following types of groups have participated in consultations for TWRI projects:

The TWRC's database for invitations for public consultations contains contact information for 6,000 people. While the corporation does not track how many people attend each meeting, all projects are subject to the corporation's Public Consultation and Participation Strategy. The strategy stipulates that any projects will require identification and notification of interested parties though the issuance of public notices as well as the establishment of a venue for these parties to provide input into the project process. Key informants noted that some consultations have drawn hundreds of participants.

In addition to regular public consultations, the TWRC holds stakeholder meetings with those groups who have expressed an on-going interest in the waterfront revitalization. Many of these groups have been advocating for the protection and improved management of Toronto's waterfront areas for years, often prior to the establishment of the TWRI. These stakeholder organizations/groups have included, for example:

In August 2006, the TWRC organized Quay to the City, a 10-day event partly funded by the federal government. The event was intended to showcase the firm West 8 + DTAH's design vision for Toronto's central waterfront. The objective of the event was to allow the citizens of Toronto to immediately experience some of the benefits of the new waterfront design. Essentially a large-scale public gathering and art installation, Quay to the City involved the replacement of roads with bicycle lanes, a kilometre-long stretch of 12,000 red geraniums and a picnic lawn. A four-storey sculpture was built with bicycles highlighting the temporary new section of Martin Goodman Trail.

The TWRC also holds design charrettes, which are intensive workshops in which various stakeholders and experts are brought together to address a particular design issue.43 In 2007, the TWRC held the Cherry Street Design Charrette. Five participant groups developed their ideas for Cherry Street into proposals for the review of the design committee. Each group included several community members (from environmental organizations and neighbourhood associations), technical staff from the Toronto Transit Commission and the City of Toronto, and consultants from the West Don Lands Environmental Assessment team.

Key informants interviewed for this evaluation singled out as a particular success the degree to which the TWRI has involved the public and interested stakeholders. For example, the community was heavily involved with architects in the planning for the Don River Park. Several changes were made to the plan after consultations with residents and community groups.

In the focus group of members of community organizations and neighbourhood associations, there was general consensus that the community consultations and level of engagement of stakeholders and the community had been excellent. While there were often competing visions of the future of the waterfront, most members of the focus group felt that the process of planning had been open, inclusive and iterative. One participant found the consultations for the West Don Lands and East Bayfront Precinct Plans very engaging and inclusive, noting: "It was one of the most positive and constructive consultation processes I had ever been involved in. We could see our ideas being accepted or considered."

Other participants in the focus group felt that the process of consultations had actually helped to bring community members together, and to create a new public conversation about the waterfront. As one participant noted, the process had been a "huge community builder." Further, the process was said to have helped to generate a new discussion in Toronto on what constitutes good design and good architecture, and how they can benefit the city.

Focus groups found that residents of the waterfront area were often aware of TWRI projects that had been completed, especially Ireland Park and the improvements to John Quay and York Quay. One focus group participant had attended a TWRC public consultation, while the remainder were either unaware of the existence of such consultations, were uninterested, or felt that the "outcomes were already pre-determined" and that their participation would make little difference in the revitalization.

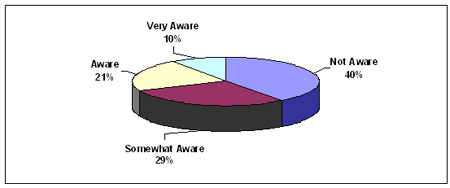

Among those waterfront area businesses surveyed for this evaluation, 60% of respondents had some level of awareness of the TWRI activities (Figure 3). When asked which specific projects they were aware of, Harbourfront Water's Edge Improvements were most frequently cited. Forty-one percent of respondents stated that they were not interested in participating in public meetings or consultations for future waterfront projects.

Figure 3. Extent of TWRI Awareness among Businesses Operating in the Waterfront Areaa, b

a Source: R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. 2007. Business Survey, Toronto.

b n = 297

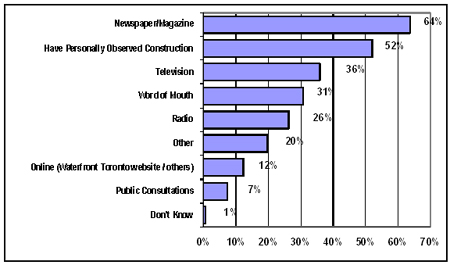

Among those business survey respondents who were aware of the TWRI, newspapers and magazines were the most frequently mentioned medium through which respondents had heard about the revitalization projects, at 64% of respondents (Figure 4). Roughly half (52%) had also observed some of the construction projects personally.

Figure 4. Proportion of Respondents Who Heard About the TWRI through Different Methodsa,b

a Source: R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. 2007. Business Survey, Toronto.

b n = 179, asked only of those respondents aware of the TWRI

Business survey respondents were somewhat less aware of the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative Precinct Plans than they were of the Initiative itself. Among those respondents who stated that they were aware of the TWRI, 45% stated they were specifically aware of the Precinct Plans.

It should be noted that the TWRC's commitment to public involvement and the considerable media attention the revitalization has garnered may not have significantly increased the visibility of the federal role in waterfront revitalization. While residents in focus groups had general knowledge of waterfront revitalization activities (and were able to list specific TWRI projects), there was a lower level of awareness that the federal government had a role in these activities.

Media coverage

Toronto's waterfront revitalization has garnered significant media attention. Media coverage has been primarily project-specific, and little attention has been given to the broader TWRI or of the federal government's role in the initiative. Most notably, the Toronto Star has regularly commented on on-going projects, including some criticism of the perceived slow progression of the projects. Community newspapers in Toronto have also covered revitalization activities in the area.

Increased usage and accessibility of the waterfront area as a result of the TWRI can be examined through a number of indicators: an increase in park, recreational and commercial space; new public transit capacity; an increased number of residential housing units; and based on the views of businesses and others.

Parks, Recreation and Greenspace

According to the Central Waterfront Public Space Framework, over 400 ha (1,000 acres) of parks are planned to be developed in Toronto's waterfront area through the TWRI. The TWRC has an official "parks first" strategy, with the intention of developing highly visible parks projects in the beginning to build public confidence in the progress of the waterfront development44 and to spark further development. Table 8 shows the TWRI parks planned, under construction and completed that have included federal funding, and their size.

Project Name |

Size |

|---|---|

| Planned/Under Construction | |

| Don River Park | 8 ha (19.6 acres) |

| Sherbourne Park | 1.5 ha (3.7 acres) |

| Port Union Waterfront Park | 3.5 km (2.2 miles) |

| Lake Ontario Park (includes Tommy Thompson Park) | 375 ha (925 acres) |

| Commissioners Park | 17 ha (41 acres) |

| Mimico Linear Park | 1.1 km (0.7 miles) |

| Completed | |

| Ireland Park | 213 m x 91.5 m (700 ft by 300 ft) |

a Source: TWRC

A variety of opportunities for recreational activities are planned through the TWRI, and some are now in use. Two regulation-sized fields as part of the Transitional/Interim Sports Fields project are complete as well as the Western Beaches Watercourse Facility. Additions to the Martin Goodman Trail, trail work in Tommy Thompson Park (additions of 4.7 km) and the Port Union Waterfront trail link (1.4 km) have also been completed.

Residents of the waterfront area indicated that they have enjoyed some of the completed TWRI projects. Many residents stated that they regularly walked, roller-bladed or jogged along the waterfront and had made use of the additions to waterfront trails.

The federal government's funding priority areas of parks, recreation and public spaces seem to reflect resident concerns over the current lack of these types of spaces in the waterfront area. For example, one focus group participant said that green spaces and recreational spaces were in short supply in the downtown area. Another felt that younger families have started living in the waterfront area, but that there are very few places for them to enjoy the outdoors.

Residential Development

Significant residential development through the TWRI is planned for the East Bayfront and West Don Lands areas. While Precinct Planning for both the West Don Lands and East Bayfront was funded in part by the federal government, federal funding is not being used to fund planned residential development. According to the Precinct Plans, there are approximately 6,000 residential units planned for the West Don Lands, and 6,300 for the East Bayfront areas (Table 9).

| West Don Lands Precinct | East Bayfront Precinct | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum number of affordable rental units | 1,200 |

1,260 |

| Minimum number of low-end market units | 300 |

315 |

| Number of market housing units | 4,500 |

4,725 |

| Total number of units | 6,000 |

6,300 |

a Sources: Urban Design Associates, West Don Lands Precinct Plan.

Koetter Kim and Associates, East Bayfront Precinct Plan.

According to City of Toronto data, construction of more than 30,000 residential and mixed-use units was planned for the waterfront area from 2002 to 2007. Again, however, the extent to which the TWRI impacted on this development is not known. Table 10 displays information on residential/mixed-use development plans for the Toronto waterfront area.

| Year | Residential and Mixed-Use Projects |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Projects | Total Proposed GFAb (m2) | Total Number of Proposed Units | |

| July 1, 2002-Dec. 31, 2002 | 15 |

2,499.18 |

2,057 |

| 2003 | 30 |

150,735.67 |

5,667 |

| 2004 | 20 |

65,087.27 |

2,727 |

| 2005 | 29 |

135,557.61 |

12,357c |

| 2006 | 22 |

28,816.84 |

4,601 |

| Jan. 1-June 30, 2007 | 8 |

37,482.19 |

3,252 |

| Total | 124 |

420,178.76 |

30,661 |

a Source: City of Toronto, Land Use Information System (IBMS), July 1, 2002-June 30, 2007.

b GFA = Gross Floor Area

c This includes the West Don Lands proposal at 185 Eastern Avenue, which includes 5,720 proposed residential units.

Public Transit Capacity

The Central Waterfront Secondary Plan has laid out a "transit first" strategy for Toronto's waterfront. Light Rail Transit (LRT) services are to be constructed at the earliest stage of the revitalization process in areas including the East Bayfront so that transit services are in place as the first developments are occupied. This is felt to encourage non-auto travel patterns from the outset. Roadways are to be kept as narrow as possible and transit, pedestrians and cyclist needs will take priority above those of automobile traffic. Consistent with the TWRC's transit strategy, the Precinct Plans for both the West Don Lands and the East Bayfront include a commitment to make public transit accessible within a five-minute walk for all residents of the areas. The proposed exclusive streetcar line on Cherry Street allows for public transportation access to the central part of the West Don Lands.

In 2002, almost 80,000 persons per day entered or exited the subway through Union Station, making it the busiest subway station in Toronto.45 Issues of surge ridership at peak times and awkward pedestrian flows to and from the subway prompted the development of a second platform at Union Station to alleviate the congestion. Design and construction of this second platform, involving federal funding, is ongoing.

Quay to the City and other Evidence of Increased Accessibility

Data gathered for a recent evaluation of the Quay to the City event suggested that this 10-day event attracted people to the waterfront area. For example, bicycle traffic increased from 159 bicycles per hour at peak times for Queens Quay eastbound, and 189 westbound, from 45 and 14, respectively, for the same time of day prior to the event.46

Key informants interviewed for this evaluation also pointed to other indicators of increased accessibility and usage. These included increased pedestrian traffic at John Quay and York Quay (Martin Goodman trail), the usage of the Western Beaches Watercourse Facility, and the development of public transit in the Cherry Beach area.

5 Government of Canada, Strong Leadership.

6 Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Federal Government's Response to the Mills Report.

7 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Results-based Management and Accountability Framework, p. 4.

8 Mercer Delta Organizational Consulting, Review of Alternative Governance Structures, p. 30.

9 £1.86 billion is equivalent to approximately $3.78 billion (2008) Canadian dollars.

10 Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Task Force, Our Toronto Waterfront, p. 63.

11 Oliver Wyman, Value-for-Money Audit.

12 Wernstedt, pp. 347-369.

13 Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation, Our Waterfront.

14 Canmac Economics, Waterfront Development Corporation Limited.

15 London Docklands Development Corporation, Regeneration Statement.

16 London Docklands Development Corporation, Employment Monograph.

17 Mercer Delta Organizational Consulting, Review of Alternative Governance Structures.

18 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Policy on Transfer Payments.

19 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Frequently Asked Questions.

20 Infrastructure Canada, 2006-2007 Departmental Performance Report.

21 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, From Red Tape to Clear Results.

22 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Policy on Transfer Payments.

23 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, From Red Tape to Clear Results.

24 Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation and the Toronto Transit Commission, Toronto Transit Commission Union Subway Station Second Platform.

25 Oliver Wyman, Value-for-Money Audit.

26 Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Audit of the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative.

27 Hara Associates, Market Failures.

28 National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy, Cleaning up the Past.

29 DeSousa, Measuring the Public Costs and Benefits.

30 Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance, 2006 IDBF Club Crew World Championships.

31 As of June 2007

32 Subject to a different federal EA process prior to changes in the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act in 2003

33 The Ontario Environmental Assessment Act applies primarily to public sector proponents including Ontario government ministries and agencies, municipalities, conservation authorities and public sector utilities.

34 L.M. Bruce Planning Solutions, Environmental Assessment Requirements.

35 Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation, Sustainability Framework.

36 Swedish Trade Council, Sustainability Review.

37 Waterfront Toronto, Green Specification.

38 A highly efficient system of producing heating/cooling systems at a single central utility plant for distribution to other buildings through a network of pipes. Users extract energy from the distribution system for their individual heating and cooling requirements.

39 "LEED® (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) gold certification" indicates that the Canada Green Building Council must certify that all buildings achieve mandatory sustainability standards.

40 "Vegetated roofs" or "green roofs" are thin layers of living vegetation installed on top of conventional flat or sloping roofs. Green roofs protect conventional roof waterproofing systems while adding a range of ecological and aesthetic benefits.

41 Canada Green Building Council website.

42 Grant, Mixed-Use in Theory and Practice.

43 Zimmerman, Alex, Integrated Design Process Guide.

44 Vogel, Greening Waterfront Development.

45 Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation and the Toronto Transit Commission, Toronto Transit Commission Union Subway Station Second Platform.

46 Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation, Quay to the City.